Beatles’ ‘Revolver’ Box Brings ‘Get Back’ Treatment to Band’s Creative Breakthrough: Album Review

The Beatles’ ‘Get Back’ movie and accompanying book, box set and ballyhoo capped the proverbial long, winding road of 50th anniversary deluxe editions that began five years earlier with the ‘Sgt. Pepper” and continue (taking into account pandemic delays) with the White Album and “Abbey Road”. It felt like the end – the “Get Back” sessions showed in excruciating detail why the Beatles broke up, and the resulting album, “Let It Be”, coincided with the April 1970 announcement of the band’s split and still had a requiem-like air about it.

But retrospectives don’t have to follow any rules, much less a timeline, and the release today of a lavish box set documenting the band’s 1966 classic “Revolver” suggests the series is likely to go backward in time through the rest of the band’s discography. And what a starting point: not only is ‘Revolver’ arguably the band’s best album (fans are usually torn between it and ‘Abbey Road’), but it’s also the one where they really started to venture. And while there’s no video of the sessions, the set uses a “Get Back” style approach to several of the songs, where listeners can hear “Yellow Submarine” evolve from a depressing lament. to the familiar flippant children’s anthem, that “And Your Bird Can Sing” once had a blatant Byrds reference, and “Tomorrow Never Knows” was originally much slower — and even more trippy.

More Variety

A gloriously overstuffed companion book includes an exhaustive recap of the songs’ genesis and progression in the studio, a lengthy (and oddly self-referential) essay by Questlove, and an abundance of photos from the sessions and the era – including a particularly interesting one of Paul McCartney wearing sunglasses, low on his knees, looking at the competition’s latest album, the Rolling Stones classic “Aftermath”.

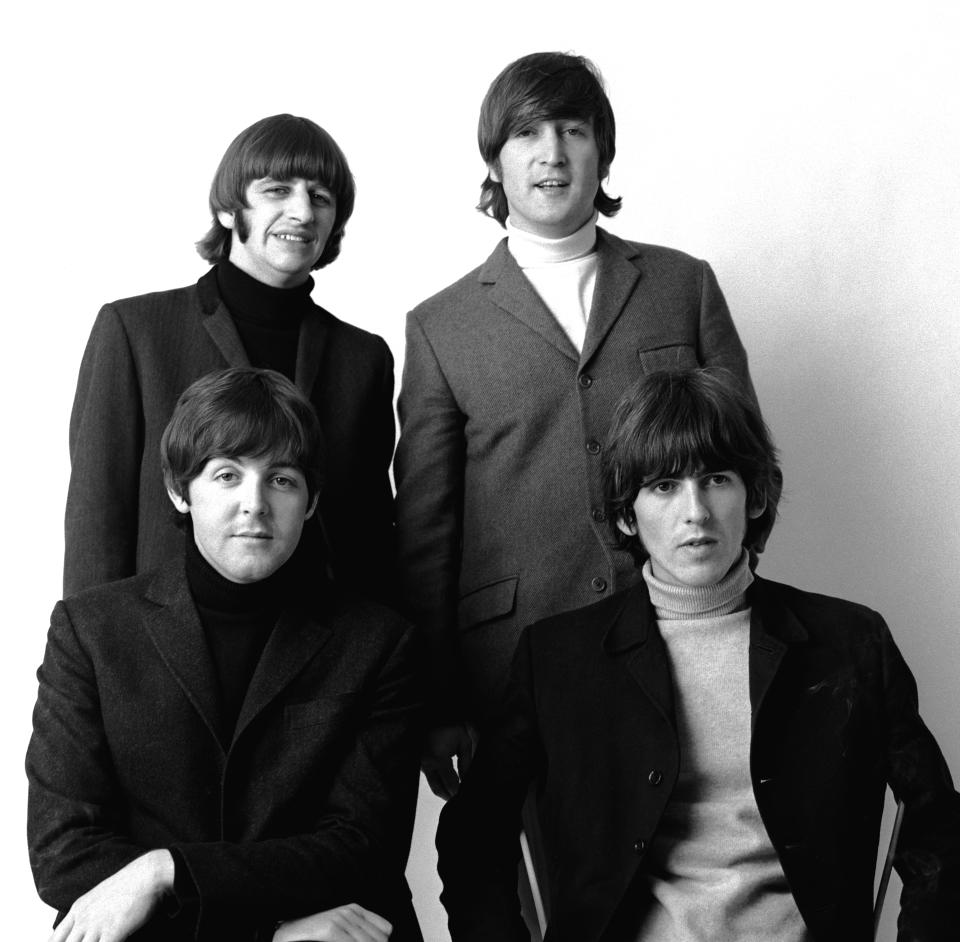

Along with the blossoming of the Beatles’ creativity, “Revolver”, released in the summer of 1966 at the height of the Swinging London era, also documents the growing influence of weed and LSD on the group. In 1966, the upside-down guitars on “I’m Only Sleeping” and especially the hallucinogenic effects on “Tomorrow Never Knows” were brand new sounds, but the band also brought a similar sense of expansion to the most popular songs. singles from the album: the effervescent pop of “Got to Get You Into My Life”, the baroque innovation of “Eleanor Rigby” and rockers like “Dr. Robert” and “Fisc”. And as some of the photos in this box set’s stunning companion book strongly suggest, The Beatles – aged 25 (John and Ringo) and 23 (Paul and George) at the time of the album’s recording – were tall as kites a lot of the time.

But anyone reading this has probably known “Revolver” inside and out for most of their conscious life. And while there’s a new mix by Giles Martin (yes, the son of Beatles producer George) and a pristine mono version than ever, what’s really special here is the aforementioned book and especially the excerpts , many of which have eluded bootleggers in the half-over a century since illicit Beatles releases began hitting the market. There are alternate versions of all but one of the 14 songs on the album (“Good Day Sunshine”) as well as the contemporary single “Paperback Writer” / “Rain”: demos, different takes or mixes, backing tracks, banter in the studio and even the instrumental version of “Rain” as it was originally recorded, before it was slowed down for the released version to make it even rainier. The instrumental version sounds incredibly fast, almost comedic, as if the Chipmunks were playing instruments (to use a contemporary simile). Ringo’s drumming on the track, arguably his finest in the Beatles canon if not his entire career, is truly astonishing.

Fans are already familiar with four of the alternate versions included here from the second volume of the Beatles’ 1996 “Anthology” series, including the most fascinating: the radically different first take of “Tomorrow Never Knows.” It’s much slower, more trippy and less aggressive than the familiar version, with hazy “Rain”-like guitars and a languid but heavy tempo, similar in shape to the final version. The song’s famous tape loops are missing, though a repeated backwards guitar line runs throughout; Lennon’s voice barely fits into the rhythm. It’s perhaps the most compelling release in the band’s canon, and the fact that it’s the first song recorded during the “Revolver” sessions is clear evidence of the band’s progression over the six months. since they were in the studio. (Lennon would also usher in their next phase with “Strawberry Fields Forever” several months later).

The other dropper here is much more conventional for 1966: an earlier version of Lennon’s “And Your Bird Can Sing”, highlighted by a 12-string electric guitar that sounds remarkably like Byrds, and shows how the influences from both bands are beautifully collaborative. on top of each other were at the time – Roger McGuinn bought a 12-string Rickenbacker after seeing George Harrison play one in ‘Hard Day’s Night’ and based the whole band sound around it, and here the influence is sealed off. (It’s also possible they enjoyed the “Bird”/Byrds pun, though that may be this reviewer’s wishful thinking.) A different version of the song with a much straighter tempo is also included, and another that finds Lennon and McCartney laughing uncontrollably. throughout (see comment above regarding kites).

We hear the evolution of “Got to Get You Into My Life” as it moves from an exploratory first take with John and George harmonies to a rockier, guitar-heavy version; the progression ends with an instrumental that mixes these guitars (which were eventually dropped) with the familiar horn arrangement. “I’m Only Sleeping” goes through two instrumentals and an approximate route.

But the most striking of these is the progression of “Yellow Submarine”, which begins with Lennon’s positively melancholy demo – “In the place where I was born / Nobody cared, nobody cared — and gets more glib as he heads into the final. take. And while it may have longtime fans wondering how many times they really need to hear “Yellow Submarine” in this life or the next, it’s yet another example of how many different directions the Beatles songs could take before deciding the final. one (or, in the case of both versions of 1968’s “Revolution”, decided not to decide).

If the show does indeed go back in time from here – with fans endlessly transported back in time, so to speak – there will be diminishing returns: we’ll hear The Beatles spend less time in the studio and witness their creativity explosive in reverse, presumably ending with their debut album, most of which was recorded in a single day. There will be less experimentation, the alternate takes will be less alternate, the sounds less revealing.

But as long as there are moments like “Tomorrow Never Knows” and the laughing take from “And Your Bird Can Sing”, as long as we continue to hear those voices that we know as well as family, these albums will be a welcome visit with old friends.

The best of variety

Subscribe to the Variety newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Click here to read the full article.

Comments are closed.